Not a very inspiring title I know.

It’s the number of a 1913 railway carriage in a white stone building on the edge of a leafy glade in Compiègne, near Paris.

Made of dark wood with brass fittings, the carriage stands enshrined in its ‘carriage-house’ like a ship in a dry dock, far from the railway tracks.

But why is it there?

By the autumn of 1918, with an allied blockade biting deep into the civilian population and her troops being forced back towards the homeland, Germany was in a dire position. She sought an honourable armistice that would (hopefully) stabilise the government and stop the revolution that threatened.

In early November 1918 a politician, a diplomat, a soldier and a naval captain set out to negotiate an end to four years of destructive warfare.

After a difficult journey from Germany to Belgium and into France (latterly with a French escort who took them through the most devastated areas) they arrived at Tergnier in Picardy. There they boarded Napoleon III’s private train for an undisclosed location.

Earlier, the chief engineer of the Nord railway, M. Arthur-Pierre Toubeau had been asked by the French government to find a discrete location where two trains could be accommodated parallel to each other. He suggested a clearing in the Forest of Rethondes, near Compiègne where an emplacement had been built for huge railway guns.

And so on the morning of 8th November 1918 the German delegation felt their train stop and, looking through the windows, saw another train about a hundred metres away – that of Supreme Commander Allied Armies, Ferdinand Foch.

Over the next three days Foch and his team of senior allied commanders imposed armistice terms designed never to allow Germany to threaten France again.

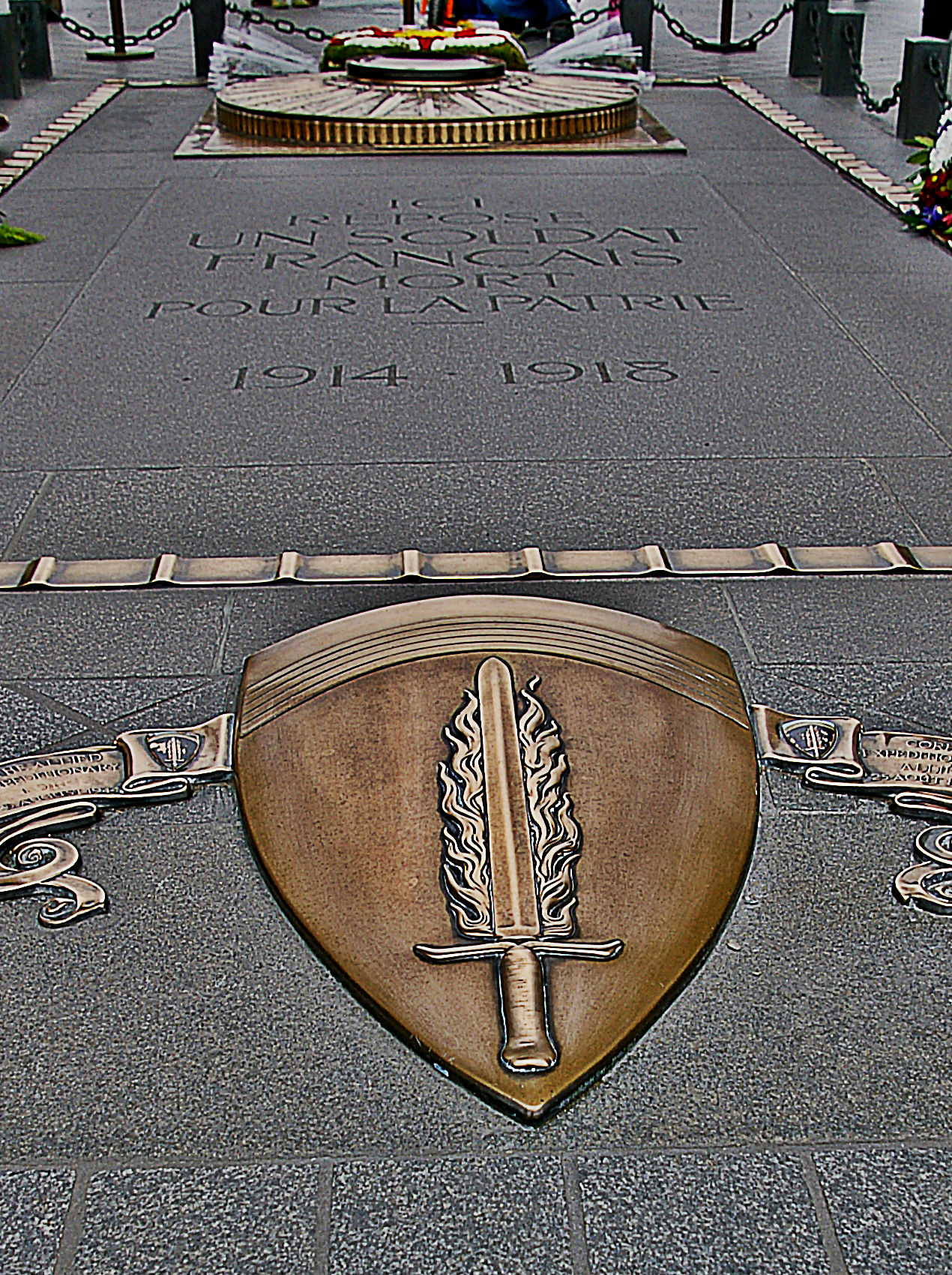

Although the fighting stopped on 11th November (henceforth celebrated as Armistice Day) it took a further six months for a peace agreement to be signed in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. The resulting war reparations crippled Germany.

The railway carriage went back into service with the Compagnie des Wagons-Lits, before being attached to the Presidential train. Between 1921 and 1927 it was exhibited at Les Invalides until moved to a specially constructed stone ‘carriage house’.

In 1940 France fell to a new German army and Hitler wanted to humiliate the French nation – much as Foch had wanted to do to Germany two decades earlier. Hitler had the railway car broken out of the carriage house and moved to the exact same spot where Foch’s train had stood.

On 22nd June 1940, he sat where Foch had and listened as the surrender terms were delivered to the French representatives. When the French agreed to sign, Hitler curtly left – posing only for a quick photograph – exactly as Foch had done.

Shortly afterwards he ordered the complete destruction of the site and the memorials around it. Strangely, only Foch’s statue was allowed to remain.

The railway carriage was sent to Berlin along with a memorial to Alsace-Lorraine and a huge inscription citing the ‘criminal pride of the German Empire’, where it was exhibited in the Lustgarten (Pleasure Garden) until 1943. After Germany’s surrender the stones were discovered and returned.

But what of 2419D?

As the bombing of Berlin intensified it was moved to Crawinkel in central Germany. Here its SS guards, under orders not to let it fall into Allied hands, blew it up and buried the pieces.

Restoration of the site was completed in 1950 and a sister railway car from the same batch (2439D) was renumbered and placed in the restored carriage building.

This article was kindly written by one of the readers of my blog, Richard Maddox. Richard brings to us his knowledge and his youth-like enthusiasm, and we hope to enjoy more of his well considered articles on important historical matters through Europe and France. If you don’t want to miss his articles make sure you “subscribe” to this blog – which means you’ll get emailed the latest articles that are published!

Great read! Really enjoyed it

Matt, thanks so much for your kind words.

Excellent post. Very thoughtfully written and really artful photographs (j’adore le drapeau tricouleure). I wish my history books had been this interesting!

We find that when traveling, we can appreciate a location so much more if we have some sense of the places history.

Thanks for your comments. As you will know the word History in French is histoire, which also means “a story”. In the play “History Boys”, history is quoted as being “just one @#% thing after another”!! Enjoy reading your blogs too! Cheers!

The sort of blog post I like, which takes you deeper into history and culture than the usual travel blog.

Richard better write some more…we’re going to enjoy them if he’s this good out of the blocks!

Thanks Jim! We had another cracker earthquake last night – especially for Hillary Clinton who is in town!

I’m a history enthusiast and I thoroughly enjoyed this well written article.

Thanks a million for your comment. I remember how at school we felt about “History” as a subject. But it should actually be just like a good book!

Great story and I love the photos. Thanks for bringing some life to history. Look forward to reading more.

Thanks for your comments guys. Bon weekend!

Good writing. A little bit of history retrieved and acknowledged.

Thanks for taking the time to write Robin! Cheers.

This is a very interesting and engaging article – a fascinating bit of history. I enjoyed it very much and feel compelled to visit Compiègne to look for 2419D.

Nice article. Good job with the history. Something I never find myself taking the extra time to get into. Thanks

What a wonderful story! It brings history to life from a unique first-hand view…and it makes excellent reading. Thank you for sharing this!

Apart from the History Lesson, its great to read all the

offers that other travel blogs can offer private travellers.

Many thanks to you all. So interesting as travel is one

of my passions.

I love these type of looks back at history. They are so interesting, especially if you love history, like me! It’s great to read posts like this that entertain and teach at the same time. Great post John!

Thanks Norbert for your comment! My kids used to mock me for reading “history” books, but now they are just beginning appreciate them!!! If stories are told the right way, then history becomes fun! So Richard’s article was most pleasing and happy to share it.

Hey, really great blog post… I’ve enjoyed reading through your blog because of the great style and energy.

I actually work for the CheapOair travel blog. If you’re interested, we would love to have you on as a guest blogger. Please send me an e-mail: gchristodoulou(at)cheapoair(dot)com, and I can give you more information. Looking forward to hearing from you.

Thank you for sharing this well-written retrospective. 2419D is no longer just a random number, but a piece of history.

Thank you John for an extremely interesting and well-written post. But I’m left with a puzzle regarding Dining car 2419D: History tells us that this was the railway carriage used to facilitate the French surrender on June 22, 1940. But in the joint NBC/CBS radio broadcast of the event, “live” from Compiegne, the carriage number is given as D2604. I know it’s a small point but it seems incredible that two well-respected American foreign correspondents (William L Shirer was one of them) could make such a glaring error, especially as they were less than fifty yards from the carriage at the time of the broadcast. Does anyone have an answer to this puzzle?

Hello Peter from Australia

Right – First things first. Call me chicken if you want but I’m not a historian, just someone with an interest in history, nor a railway buff and I’m certainly not going to take on NBC/CBS and cast aspersions on Mr Shirer’s reputation!

I’m honestly baffled by this. As you say William L Shirer is a much-respected journalist and historian. The reproduction carriage clearly shows the numbers by the door and in the form of four digit number and then the letter ‘D’. A book I have in my possession ‘Le 11 Novembre’ by Jacques Meyer, published by Hachette in 1964 shows (page 46) a close up of the serial number of the original dining car (No 2419 D) with the caption that it is a picture of the number on the ‘wagon authentique’ which disappeared in a fire in Berlin and was transferred to the contemporary railcar.

Given that the 1918 car was put initially returned to service, becoming part of the Presidential on exhibition in Paris before being housed in its purpose built shelter at Compiegne (from which it was broken out of by the Germans in 1940) indicates that it was clearly kept track of and its historical value known.

The Getty Images site has a picture of the carriage which they caption as around 1925

The pictures I have seen of the carriage being removed from its protective building (such as this on the First World War Hellfire Corner site) have loads of German soldiers standing in the way of the number – if I had been there I would have probably have been very frustrated and wanted to yell something like ‘Heh guys… could you a bit move … yep… just want to get the number in… thanks!’

Except of course that I don’t speak German wasn’t born and would have been arrested as a British spy.

I have found a copy of a colour picture from LIFE magazine reproduced on the French 39-45.05g website forum that shows senior German officers at the 1940 signing with a clear image of the 2419D number. Pictures of the wagon going to Berlin do exist (so far I’ve only seen them on the Internet) but the ones I’ve seen are shot from angles where you can’t see the number!

Which brings us to the replacement carriage. I must confess not to have any pictures of my own of this as although I have been to Compiegne and seen the carriage, there was (and I believe still is) a ban on photography of the Armistice carriage. An image from a Coty postcard (that I’m sure I’ve got a copy of somewhere) on the Model Railway Forum site – no stone unturned in this quest – doesn’t show the number clearly , although enlarging the image on screen you can make out the number 2419 D although it’s not easy as the view is a three-quarters one.

In short, I’m as unable to answer your question as when I started this reply! I’m tempted to say that it was a slip made during a live broadcast (I know I sometimes get numbers confused – but never on my bank statement.)

On the other hand you may have stumbled on something significant in so far as one or more of the coaches concerned may have had a previous identity, perhaps being started as a build for service elsewhere, in the same way as ships and aircraft may change identity during their construction.

What ever the truth it proves the old adage; ‘There are no answers. Only further questions.’

Sorry that my reply was so long but as you took the trouble to ask the question I believe you deserve an answer.

Only there are no answers. Only further…

Hello again Peter from Australia.

Just seen that my links to the photos have not worked in the reply above so here they are:

The 1925 Getty Image is at:

http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/3202641/Hulton-Archive

The Hellfire Corner article about Compiègne:

http://www.hellfirecorner.co.uk/clairiere/clairiere.htm

The colour LIFE Magazine image:

http://www.39-45.org/viewtopic.php?f=17&t=23643&start=15

The Coty postcard can be found at

http://www.modelrailforum.com/forums/index.php?showtopic=8735

Once again thanks for your query.

Hi Richard,

Thank you very much for your detailed and most informative reply but, as you say: ‘there are no answers. Only further questions.’ Which brings to mind a couple of theories which could possibly explain the error. Both William Shirer (reporting for CBS) and his colleague, William Kerker (the NBC journalist) had been allowed inside the old wagon-lit carriage prior to the armistice being signed and maybe that’s where they noticed the D 2604 number and mistook it as the official carriage designation. Possibly, it was Reichsbahn-allocated number for the carriage’s eventual transfer to Berlin.

Foreign correspondents like Shirer and Kerker would rarely get those kinds of facts wrong but a clue may lie in the unusual circimstances surrounding the armistice broadcast. Hitler had deemed the event to be a German radio exclusive but Shirer, who had connections within the Reichs Rundfunk (RRB, the German equivilant of the BBC) was able to get a half hour window on the broadcast circuit from Compiegne, via Brussels, back to Berlin. What is even more amazing was that Shirer was able to convince RRB technicians to route the broadcast feed to a shortwave radio transmitter where it was subsequently picked-up in New York and re-broadcast live over both the CBS and the NBC networks. More importantly, for people of our generation at least, the New York technicians had the good sense to record this historic broadcast. It remains a not just a powerful description of the French surrender but a valuable audio record of the sounds of the Forest of Compiegne — birds flying overhead, the constant drone of German Army generators, the off-mic mumurings of military bystanders — on that warm June day in 1940.

Not surprisingly, the German High Command was less than impressed with Shirer’s “scoop” — especially as it was undertaken using German broadcast facilities — and it signalled the beginning of the end of William Shirer’s days as a Berlin correspondent.

If you’re interested in listening to the Shirer/Kerker broadcast, a reasonably good quality copy can be downloaded from

http://www.archive.org

Thank you Peter for your valuable notes and comments. I’ll certainly download the copy of the broadcast.

Its interesting to see how news management was being used even then, with Hitler giving exclusives to influential foreign correspondents, especially in the light of the subsequent publication of the remarks of the US Ambassador to Britain, Joseph P Kennedy (in November 1940), writing off Britain’s ability to oppose Nazi Germany and recommending that aid to Britain should be denied.

Thank you again Peter for adding to my knowledge and in turn highlighting more avenues to explore.

Richard

[…] has been occupied for over a week. An armistice was been signed in the same railway carriage, at the same spot in the Forest of Compiègne where Foch had imposed terms on the German delegation […]